Have you ever heard these phrases at some point in your life?

- “Like I said…”

- “Please let me finish my sentence.”

- “No, you don’t understand. You are not listening.”

- “I don’t need your opinion; I just need you to listen. OMFG.”

- Etc.

We have all been there. I still do. Most of us know how to talk to other people, but we don’t listen well. A lot of conversations that we have now are just two monologues. Research shows that we would only retain 25 to 50% of the information of what we hear.

No subject in school would teach you how to listen. Instead, we were taught to memorise and often regurgitate information later, completely forgetting almost everything we learned. But there are thousands of training on how to speak publicly, talk confidently, etc. In the context of moderation, your employer/boss would often emphasise questioning skillsets, managing client expectations and delivering impactful debrief post-group discussions. However, they don’t stress enough that moderation requires conscious listening, which is the most significant task of a moderator.

You invite your participants because you want to understand and learn from them. They agree to participate because they want to be heard (and get the monetary token, of course). Yet, we don’t want to listen to them, which is weird.

People love to hear themselves talk. It is rare to find someone who is a genuine listener. We are programmed to answer or ask questions with our opinions or merely follow our discussion guide/pointers. People are so scared they won’t be heard, so we try to grab every chance we can get to speak up. People genuinely want to be heard in a world where everyone is talking.

Listening is one of the essential skills that you can learn. The level of listening we should aim for is to understand completely, immerse, learn and energise the people we talk to. The participants should be the main star of the interview or focus group discussion. If you talk more than your participant, you are not doing a good job. If you can’t remember what was said after the interview ended, you are not listening.

This post aims to share some listening skill tips to become a good moderator/interviewer and encourage meaningful conversation with others.

Importance of Listening

How well you listen significantly impacts your life; it will make you absorb the information quickly, improve your job and relationship with others, and potentially save your life.

- Make them feel heard/appreciated – In Kantar, I attended a training where we had to listen to our conversation partner (a colleague). We must listen and summarise what they say to make them feel fully understood. Just need to reiterate their point. It sounds easy, but it took quite a bit of effort because we are so used to just listening for keywords while our minds go elsewhere. But, the result of the exercise is that we feel heard and appreciated.

- Improve your communication – Imagine living in a world where people don’t misunderstand each other, especially now that everyone is taxed. Our attention span has been stunted by all the collective trauma of the social-political unrest and whatnot. Good listening would improve your communication and increase your productivity tenfold, and the world would be a much better place.

- Improve your persuasion – People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care. Someone said that who probably ripped it off from someone else. But listening would give you a better chance to come out on top, give you a competitive advantage, and make people listen to what you have to say.

- High demand – Good listeners are always in short supply, professionally or personally. They get hired instantly and scooped out of the dating pool so fast. So stop simping and practice active listening, okay, comrade?

How to listen during moderation

DO’S

- Pay attention. Do not multitask – Put your phone away, stop looking at your discussion guide and REALLY LISTEN to your participants. Try to stay conscious of it. There is no reason for you to learn how to show attention if you are, in fact, paying attention.

- Take notes – You aren’t going to remember everything. Treat it like a school lesson. Write notes, key phrases you think are essential, and feelings whenever possible. It would be helpful to get a better understanding, create a mental outline and improve your recall.

- Listen to understand, not to reply or reload – Don’t engage, listen. I am guilty of this, but I can usually catch myself doing it. Try to shut off your internal monologue. Stop your mind from being anxious to respond or come up with questions/jokes.

- Assume everyone has something to teach you – In other words, don’t be a dick and start to appreciate your participants. Everyone can teach you something regardless of who they are. You are there to learn and understand their views and experience.

- PRO-TIP: Believe that in every story you hear, there is an important lesson to help you with your life, or you are getting information about your participant’s inner world, things they don’t usually say to you or have yet to learn about themselves. This tip would help you take a special interest because there’s something in it for you now. If you adopt this mindset, you will discover how each story has valuable lessons, no matter how dreadfully dull it may sound.

- Ask open-ended questions – Good listening should be a two-way dialogue and interactive. It is not just staying quiet like you are talking to an ATM. Ask open-ended questions to clarify and understand. Usually, our discussion guide would cover the basic 5W1H (What, when, why, who, where and how). “What was the best part of your job?” will get you a different answer than “Do you like your job?”. But be careful with WHY. We will cover this in detail later on.

- Be yourself but with a heightened sense – Neutral is king. Talk in your language. Respond to how you would typically respond. Sometimes, I get so preoccupied with maintaining the appearance of listening rather than actually listening. It isn’t easy and would take tons of practice.

- Observe the non-verbal cues – Facial expressions, tonality, gestures, and postures would tell you a lot about your participants. Use your eyes and your ears well.

DON’TS

- Don’t interrupt – As a moderator, understand that listening is less about the listener (moderator and observers) but more about the participant. We need to help the participant to articulate their thoughts. Interrupting them is counterproductive; it is disrespectful, they tend to lose track, and you won’t get anywhere. You’ll be surprised how often people know the answer to their problems if you give them space to sort it out.

- If they stray from the topic – Give them a gentle nudge. Say something along the lines: “Sorry to interrupt, but I’m just curious. Could you tell me more about X?”

- If they talk in circles –This usually happens when they think they are not making their point. Try to summarise it back to them. If you understood them, they would magically stop repeating the same things over and over.

- Don’t be a parrot – Some people do this, but I’m not too fond of it because I feel it is patronising. If you do this when talking to me, I would feel like you are ticking a “mental checklist” to make me feel heard instead of listening. However, parroting can be helpful if you are counselling someone or in a disagreement, but that’s not the case when you are moderating. If you parrot it back when some participant just told you why they hate their rice cooker, it would probably put them off, and you may come across as judging. You are not a parrot or a Talking Tom app. But, if you are unclear, you can summarise to ensure you understand them correctly after getting the participants’ feedback.

- Don’t add your experience/opinion/advice – Nobody cares about your opinion/life story/advice if you are a moderator. That’s not your job.

- Exception: If you are moderating a particular group, i.e., kids or teenagers. You might need to share a common experience to bond and encourage them to open up to you.

- If the participant asks for your opinion, reassure the participant that you want to understand their problem first so we can solve it in the future.

- Don’t make intense eye-contact or nod like a Delhi scammer – Or don’t be creepy. If you feel like you would listen better if you held eye contact, or if you feel like acting the part would change how you feel inside, then, by all means, do it. But if you are not comfortable, don’t worry about it. Do whatever is natural when you are listening.

- When you learn about communication skills, usually, they would teach you to make eye contact or nod as much as possible. But what is missing from this is the acknowledgement of cultural differences. For example, in Western cultures, eye contact is highly encouraged. In Malaysian cultures, however, it can make someone feel threatened and uncomfortable. Use it sparingly, as it shows that you are concentrating on your ears’ usage than your eyes when you are listening.

- Do not nod your head excessively. It would feel a bit contrived and distracting if you take it too far.

- Don’t overdo your listening noise/gesture – Be mindful of your verbal acknowledgement sounds/gestures. Please don’t overdo it, and make sure that it is not disruptive/intrusive, especially when you moderate an online focus group.

- Some carefully timed time noise can show that you are listening, like “I see”, “Oh”, and “Mm”.

- Don’t use “I know” or “Yes, you are right”. Be neutral.

- Don’t use close-ended questions – This is the antithesis of qualitative. Using close-ended questions can close down a conversation quickly.

How do you probe and ask follow-up questions?

- Know your discussion guide well – There’s no other way around this. I always thought asking questions was a sign of good listening. But when my goal becomes asking questions, I think about good questions while the participant is talking, which makes me lose focus on listening. Be sure to know the objective for each section and what you hope to achieve from it.

- Ask follow-up and clarifying questions when you don’t understand – Well, instead of just assuming the answer. The participant would feel like you care about their opinion (which you do), and you get a more accurate understanding.

- Encourage discussion – Discussion is beautiful, and we should celebrate it.

- When your participants have a different opinion – Ask how the other participant feels or reacts to the issue/problem. What have they done differently, and how did the difference serve them? The aim is to understand the differences, not to win an argument.

- When your participants have some opinions – Tease out the different levels of pain and their coping mechanisms. What have they tried?

- Use conversational language, not research/marketing / therapeutic language– Use the language of how you talk to your friends/colleagues or parents. If it doesn’t sound natural, or your response sounds like something you read in a book, it feels manufactured, like you are not responding from a genuine place, and it might come across as impolite and fake.

- Use “What happened” instead of “How did you react.”

- Say, “Oh shit, that must be terrible”, instead of “I bet that is an extremely negative experience. On a scale of 1 to 10, how painful is that experience?”

- Don’t use why – Why? Because why is rude, judgemental and offensive. Qualitative is indeed all about the pursuit of “why?”. But when you ask “why” questions, many people feel it is patronising or take it as a sign of disbelief or judgment and can become more hesitant to talk about the subject matter. For example, “Why do you like tea?” would immediately put your participants to justify why they like tea and that you don’t understand how they could enjoy it or even think they are wrong for liking it. If you ask, “What do you like about tea?” – it is not passing judgment, and you are just curious about something they like. “Why” is accusatory and leads to your participant becoming defensive or being forced to justify their opinion and to come out with a “good answer” on the spot. Instead, rephrase it in another context, such as;

- “How did you feel?”

- “How did you come to that conclusion?”

- “What made you choose that?”

- “What were you thinking at that time?”

- “What did you do to solve that problem?”

How to improve your listening skills

The first thing you need to acknowledge is that listening is hard and takes a lot of hard work. Just remember that it may not work the same way for everyone. Find your style and work on it.

Most online courses usually will cover this topic. And the price is not cheap. I am a big believer that you shouldn’t have to pay for knowledge, so below are all free tools/steps that you can use to improve your listening skills:

- Evaluate, acknowledge and improve – If you are a moderator, ask your project management team/colleague to provide you with the session recording you just moderated. I cringed when I saw it because my voice sounded weird in recordings, and sometimes, I was not listening at all. I just wait there to fire my next salvo, or am busy looking at the discussion guide. You can also read the transcript if you don’t have time to watch the recording.

- Take an interpersonal communication course – Take a basic communication course that includes communication/listening skills, conversation, cultural/gender influence, etc. I suggest starting with Open Educational Resources or other free online courses like Edex, Coursera, Udemy, Linkedin Learning, etc.

- PRO-TIP: My best way to learn online is to check with those paid courses’ syllabus, list them down, search manually and study on your own.

- Watch talks/videos – Some of the videos that I found helpful:

- Read books – There are a lot of books about conversation and listening skills online.

- PRO-TIP: There is a free pdf/e-book online for almost everything; you need to know how to search. Google the title, edition & author by “whatever you are interested in + filetype:pdf”. Works wonders.

- Go subless – Try to watch your favourite TV shows without subtitles. It would train your brain to listen and understand the shows. Plus, you won’t get distracted trying to read the subtitles and watch what’s happening the whole time. Or try to listen to mumble psychedelic bands like Tame Impala or Alt-J and figure out their lyrics.

Final Word

Real dialogue and moderation is an art; the most important part is listening. If we started to practice listening, we could learn so much.

You will inevitably struggle or say the wrong thing. A lot of this would come from experience, and no one has all the experience. Give yourself as much patience and acknowledge that it requires a lot of hard work. But know that we applaud you for trying to improve your communication skills.

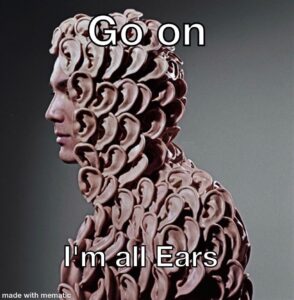

If you have a different opinion, let us know. If you have a better way, I’m all ears. Thank you for listening. Cheers.